There is a false dichotomy that often appears in lectures and texts that talk about new management models, agile methods, etc. The text goes something like this:

It’s no use copying practices from other organizations or defining working methods, what matters are the principles.

In English there is even a common term (1520 mentions in google): Principles over practices.

Experience shows that this dualism, or this attempt to put one thing before another, is more of a hindrance than it helps. Let’s imagine two stories.

Case 1

A company that develops software for third parties, belatedly realizes that if they don’t start adopting agile methods they will be left behind in the market. They hire courses to certify their project managers and start running Scrum ceremonies. Everyone knows that there is something called an agile manifesto with values and principles. On a day-to-day basis, habits, culture and organizational structure create the feeling that the ceremonies and methods are “just for show” and everything is the same or worse than it was before.

Case 2

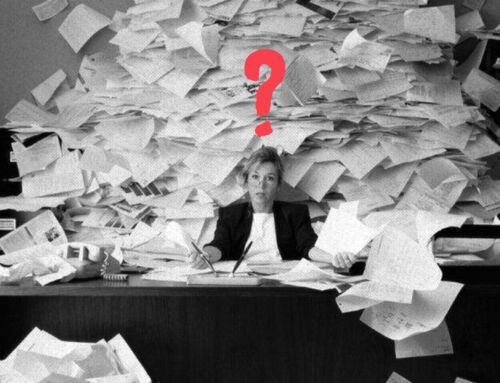

Directors of a large cosmetics company believe they need to improve team collaboration and increase innovation in all areas. For this, they are inspired by the principles of Modern Agile and hire workshops to help people understand the concepts and create practices and solutions that “make people sensational” “deliver value at all times” “try and learn fast” and “make security a prerequisite”.

During the workshops some ideas for new organizational practices are conceived by the participants. Over the next few months, people are arguing about how each principle applies in everyday life. After a few months, little has changed, except for a large, beautiful mural painted in the lobby with the Modern Agile wheel.

Analysis

In the first case, we have an investment in punctual and superficial learning of agile methods that clash with other practices within the company. We have an organizational design that emerged from very different assumptions than those in the agile manifesto. Changing this design goes far beyond certifications and the adoption of some rituals by development teams.

In the second case, we have a naive attitude of thinking that if people get to know new principles that will guide the company’s work from now on, everything will change. Without concrete changes that exclude practices, methods and policies that hinder collaboration and the adoption of practices that promote collaboration and innovation, there may even be good intentions, but they are not carried out.

The two cases show that practices and principles are interdependent. One does not exist without the other. It is the “why” and the “how” that weaken when the other lacks strength.

Two concepts need to be clarified to understand how this false dichotomy is sustained and is so common.

Gi Joe Fallacy

In the 80s I was watching a cartoon on TV called GI Joe, it ended with a moral lesson that always used the same cliché:

“Now you know. And knowing is half the battle”

And that’s the GI Joe fallacy. Knowing something doesn’t necessarily make you win the battle. In the field of studies on human behavior, it is already well proven that there is a separation between knowing something and doing something. A good part of our decisions happen on the so-called autopilot (Kahneman’s System 1).

When we say out loud that we believe in the values of the agile manifesto, it doesn’t mean we operate from them. That’s not hypocrisy, it’s just how the human mind works. In addition to the subjectivity that values bring and that allows people to justify opposing behaviors by saying that they are following them, we have the fact that we are constantly looking for explanations for automatic and habitual behaviors. We are optimized to justify all the time.

When we believe this fallacy, it is much easier to maintain that we need to focus on principles, because knowing and believing in them, we will change our behavior. However, it’s not really how it works.

Emerging Practices

With the popularization of complexity science, and especially within the agile movement of the Cynefin model, a lot of people started talking about emerging practices. It strengthened the belief that in the context of organizational design, all problems are complex and therefore demand emerging practices. In other words, you cannot copy and paste best practices or good practices. All practices need to emerge from the specific context of that organization. A full plate for those who were already fans of the “it wasn’t invented here” syndrome.

Another interpretation I prefer is that while we cannot copy and paste best or good practices, we can look at patterns that emerge in a given field and use them to help us develop our practices in our organizations.

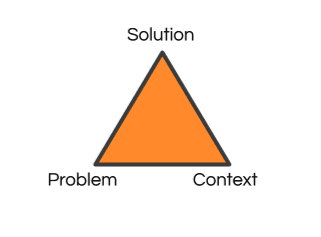

Here it is time to clarify a concept that is often used here at Target Teal. The meaning we use for a pattern is not a “standard” (a pattern to be followed) nor “default” (an initial definition), it is just “pattern” (something recurring). An Organizational Design pattern is a solution that emerged in similar contexts to solve similar problems. It is by no means a recipe. So it is not a best or good practice.

Analyzing the context and problem in which a pattern emerged is key to avoiding bizarre things like suggesting to a sales team the use of Scrum. Thus, in similar contexts and problems, we look for a pattern that can serve as an inspiration for the proposition of a new organizational practice.

Creating practices from scratch, without references to other standards is throwing away a lot of knowledge and limiting your creative capacity. Creation is more of an act of bricolage*, of taking something apart and putting it together to make something unique. But this is only possible if you know in depth practices that can be useful in your context. Rushing to courses that sell certificates goes against that.

Believing that we can have emergent practices just looking at principles, and relying on a small repertoire of people in an organization, usually leads to failed organizational transformation processes. The false dichotomy between principles and practices gives a beautiful guise to a disastrous strategy.

It’s not one or the other, it’s both

Principles are abstract, vague and subject to multiple interpretations. Alone they do not describe the specific behavioral changes that are desired. They don’t offer triggers or incentives that help people change the way they operate. When used in conjunction with practices they are important because they give meaning to what we are doing. They inspire us and most importantly, they can help us adapt practices to the contexts and problems we encounter.

Practices can be staged and become something devoid of value and meaning. We lose hope and become skeptical when we find practices that don’t help solve problems, but are present in some form, just because they’re a fad. When the principles are intrinsically present and are lived even if tacitly, the practices guide us and make our lives easier.

In order to honor a practice, we need to invest time to fully understand it, live its principles, and benefit from the learnings that have been distilled from the people who generously shared it. Enough of this false dichotomy.

At Target Teal we help organizations get in touch with practices and principles that are emerging in more responsive and humanized organizations. If you want our help and aren’t worried about filling the wall with certificates, let’s talk.

*Bricolage, a word of French origin (“bricolage”), means doing small jobs (usually repairs). In anthropology, bricolage is the union of several elements to form a unique and individualized element.

Translated by Tanya Stergiou

Leave A Comment