In the post “Office Drama? Understand what’s behind it” we wrote about how conflicts at work can intensify when assuming the roles Karpman’s drama triangle: victim, persecutor and rescuer. We concluded that when faced with difficult situations, we have a natural (and impulsive) tendency to take on these roles, even if they are not good for the situation as a whole.

If the triangle is harmful, what can we do when confronted with conflict? And how can we avoid taking on the dramatic roles? That is what we will respond with this text.

Recap: Anita and Joyce

In the last post we talked about some examples of conflicts at work, identified through the story of Anita and Joyce.

Anita wants to deploy new management practices in her department. Joyce wants more freedom to do her job. Both Anita and Joyce have the same need: to be recognized for good work. The problem is that the two don’t have a conversation about the situation. Both build uip assumptions about the behavior of the other, tending to negative judgments.

Anita notes that the number of campaigns launched by Joyce has been dropping (observation). From this, she concludes that Joyce is being lazy and not working as before (judgment).

Joyce realizes that Anita is asking frequent questions about her work (observation). From this, she concludes that Joyce is micromanaging and that therefore her discourse of autonomy is not consistent with her practice (judgment).

Inferring Intentions

Joyce and Anita create meanings (judgments) from what they observe in each other (observations). And it’s not just them. We do this all the time. Obviously these meanings may not be true, for they are only hypotheses, based on our limited understanding of reality.

Funny, right? Both Joyce and Anita believe that the other’s intention is bad. Curiously, we tend to think that the intentions of others are bad, while ours are always noble.

This is precisely the problem. We need to realize this automatic and unconscious behavior. By assuming that others are bad and selfish, we avoid having a difficult conversation. Interestingly, this (the conversation) is one of the most effective strategies for dealing with conflicts at work and in life.

Dialogue: a social technology to deal with conflicts at work

This is a very old, but forgotten social technology in the corporate world. Dialogue comes from the ancient Greek (dialogues) and means “through the word”, or “passage between two or more”.

When we want to have a dialogue, we must seek to investigate the situation together, without pretending to know in advance what will happen. We need to leave the certainties aside and be willing to understand how the other sees the situation. It is a posture of curiosity and appreciation.

In the case of Anita and Joyce, they could establish a dialogue to understand how each of them sees the current situation. They could also share their intentions, leaving less room for inferences.

Remember: the purpose of dialogue is to understand, not convince!

Revealing Intentions

Remember the previous post? We said that what keeps Joyce and Anita out of the roles of victim and persecutor is precisely not to reveal their intentions.

Through dialogue, both could talk and clarify their intentions. Talking about intentions gives much more legitimacy to the requests we make to people, as they tend to create less assumptions about what motivates us.

In the exemplified conflict we have the following intentions: Anita wants to implement new management practices in her department to be recognized by the rest of the company as an innovative manager. Joyce wants to have more freedom to do her job and start the projects she believes can have an impact, and then prove to her manager that she does a good job.

Of course it may not be that simple in your case. Intentions are complex and sometimes even unconscious. It is also not easy to admit some, since they can come into direct conflict with our self-image.

The Empowerment Dynamic

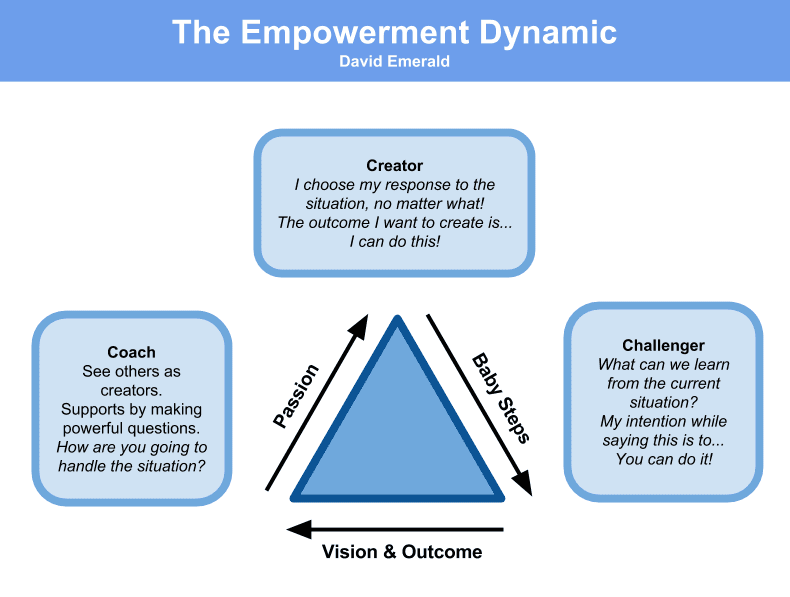

Through dialogue and the disclosure of intentions, we can take on other more functional roles that will help us deal with conflicts at work. David Emerald has identified another triangle, called the empowerment dynamic, that can be used as a reference to get out of the drama. This triangle is also composed of 3 roles:

- Creator: The creator is the center of the triangle and lives in a difficult situation. While acknowledging the observed problem, the creator understands that it can influence the end result. Unlike the victim, the creator embraces the situation as part of his responsibility and seeks to advance or take steps to get out of it.

- Coach: The coach acts as a support to the creator by asking powerful questions. The coach does not give answers or creates a relationship of dependence with the victim, as the rescuer does.

- Challenger: This role, like the persecutor, can be represented by a situation or person. The challenger causes action in a compassionate or positively confrontational way. It’s just a different perspective on the role of the persecutor. Want to turn your persecutors into challengers? Just look at them using this perspective.

Like the Karpman triangle, the empowerment dynamic aim to describe relationships between roles, not individual characteristics. We assume different roles in different contexts.

Conflicts at work are difficult. Having the guts to start a conversation about them is also. However, by avoiding establishing a dialogue, we run the risk of intensifying the drama and making the situation insurmountable.

Are you going through a similar situation? Apply the strategies described in the text and then tell us how it went.

Do you want to practice dialogue and empowerment in your organization? Reach us.

Leave A Comment