It seems like a great idea: involving your entire team in most everyday decisions. The product’s price is no longer aligned with the new market situation—so let’s gather everyone and decide together, right? Hmm… That might come at a high cost for your organization. Let’s explore how to balance participation and decision-making speed effectively.

Consensus

A consensus decision means that everyone in the group believes a particular choice is the best possible option at that moment. If even one person disagrees or thinks there’s a better alternative, you won’t have a consensus. This method can be effective because it results in decisions that everyone agrees on, but it is far from efficient. You’ll need hours of discussion, a facilitator, and a lot of energy to sustain the process.

There’s another issue with consensus that is rarely discussed in books on the topic. Without a facilitator available at all times, the people who are better at articulating their arguments, the more extroverted ones, and those with institutional power (such as a manager) will naturally have more influence in decision-making. This is hardly an ideal outcome if you aim for true equivalence in participation.

Does This Mean I Shouldn’t Involve My Team in Decisions?

If involving your team means listening to them, then the answer is yes—you should. However, listening to their input is different from trying to integrate every perspective into every decision and always reaching a consensus. That’s what you should avoid, as it will be too time-consuming and exhausting.

But I Want Them to Participate in Decisions. What Should I Do?

Types of Decisions

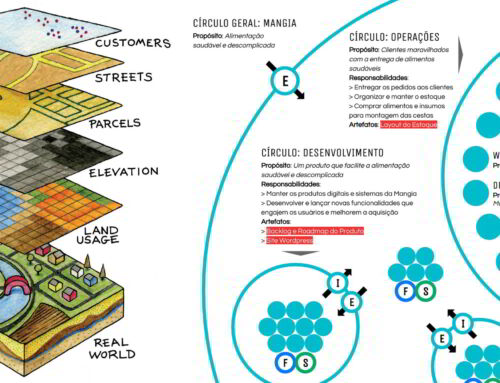

Before anything else, let’s break down the term “decision.” Organizations that practice dynamic governance (Sociocracy, Holacracy, and S3) divide work into two categories: governance and operations. I’ll add a third category, which I’ll call assignments. This distinction is important to determine the appropriate level of participation for each type.

Governance involves the organizational structure: roles, responsibilities, and policies (agreements) established by teams. A governance decision changes one of these elements. For example, defining a role called Pricing Specialist, responsible for setting product prices, is a governance decision.

Operations covers all other decisions that are not governance-related or that fall within an established role’s responsibilities. For instance, deciding the price of a specific product is an operational decision if the Pricing Specialist role exists.

Assignments refer to selecting people for roles established in governance. These decisions typically fall to managers, leaders, or coordinators. Who will take on the Pricing Specialist role? That is an assignment decision.

Involving the Team

For governance decisions, it’s essential not only to listen to your team but also to consider their concerns and integrate them. Governance structures (roles, responsibilities, and agreements) significantly impact all team members. Later, we’ll discuss how this can be done effectively.

For assignment decisions, there are two possible approaches: implement a collective process where anyone can propose a (re)assignment or evaluate a role’s performance. Alternatively, as a manager or coordinator, you can make the decision yourself after consulting your team, without necessarily integrating all perspectives.

For operational decisions, you (and others in defined roles) should make them autocratically. That’s right! You can seek advice, but don’t try to integrate every opinion.

Maximum Agility: Autocratic Operational Decisions

Most daily decisions (which are operational) are easily reversible if something goes wrong. In this context, making decisions individually is the most productive strategy—both efficient and effective. Imagine if you had to consult everyone every time you wanted to change a sentence on your company’s website! That would be exhausting and slow.

Moreover, individual decision-making provides autonomy and freedom for the person performing the role, giving them space to experiment, make mistakes, and learn.

Equivalence and Participation: Governance Decisions by Consent

As mentioned earlier, governance decisions should integrate the team’s concerns. However, consensus is not the best mechanism—consent is more suitable.

To make a decision by consent, someone must propose a solution to an identified tension (problem or opportunity). For the proposal to be approved, everyone in the team must consent to it.

Consent does not mean thinking the proposal is the best possible option. It simply means you have no objections to it. The definition of an objection depends on the social governance model you use. For example, in Holacracy, an objection is a serious harm that the proposal will cause to the group, setting it back. This is a high bar, meaning that very few things qualify as real objections.

Leave A Comment