Have you stopped to think about the incentive mechanisms in organizations? Most of companies deploy evaluation systems, annual bonuses and performance appraisals without reflecting about what really matters to individuals. Unfortunately, these practices are not compatible with the latest scientific findings on motivation. And that is the subject of this post.

First, let’s understand the difference between two categories of motivators: the extrinsic and the intrinsic ones.

Extrinsic Motivators

This is the kind of motivation that is associated with a factor outside of the activity you do, usually a reward. Examples of extrinsic motivation in the corporate world include salary, performance bonus, annual bonus, commissions, awards and even your position. Climbing the organizational pyramid is an example of competitive activity and may have extrinsic motivating factors linked to it.

We can say that virtually everything that is not generated by the activity itself is an extrinsic motivator. Including colorful cushions and video game in your office ;)

Intrinsic Motivators

Intrinsic motivation is another story. It comes from within the individual and is so close to the activity itself that it is difficult to separate it. According to Daniel Pink, the three main intrinsic motivators are:

Autonomy: corresponds to the capacity of individuals to direct their own work and have space to experiment, to err and to learn. It is associated with freedom.

Mastery: it is the impulse that moves a person to practice and develop more and more a skill.

Purpose: It is the desire to do something important and meaningful to you.

Did you feel the difference? What is most incredible is that science has proven (see below) that intrinsic motivators are more important to knowledge workers. Still, companies continue to offer benefits and more benefits to their employees. And that’s not what they really want.

Duncker’s Candle Problem

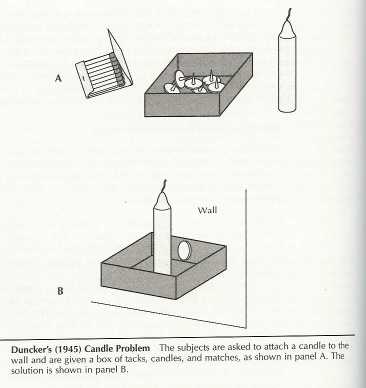

To understand more about the effects of extrinsic motivators at work, let’s look at an experiment proposed by Duncker. Participants receive a box with bed bugs, a candle and matchsticks. They should attach the candle to a corkboard so that the candle wax does not fall to the floor (when lit).

The solution to the problem requires participants to use the box of thumbtacks itself as the base for the candle. The box should be attached to the corkboard with a thumbstack as shown in the figure on the right.

What happens is that this problem requires a little creativity on the part of the participants. Initially they do not see the box as part of the solution, but only as a container for the thumbstacks.

Later, another researcher named Sam Glucksberg repeated the candle experiment, but with an interesting modification: he divided the participants into two groups: one that would received a cash prize for solving the problem more quickly and another that did not (the groups did not know each other).

What Glucksberg identified was that the extrinsic reward (the money) worsened the group’s performance. By focusing attention on reward rather than on activity itself, the group lost its cognitive and creative ability to solve the problem.

In his book Drive, Daniel Pink concludes that extrinsic motivators are bad for creative workers because they create distractions to work. What really moves us are the intrinsic motivators. We like to call this force the experience.

What is the future?

Extrinsic motivators still remain strongly present in organizational processes and structures, more influenced by tradition than by reason.

We are experiencing a time when large organizations begin to realize the importance of intrinsic factors. The movement of responsive and evolutionary organizations are examples of this self-consciousness.

Target Teal helps other companies build more collaborative, innovative, experiment-based environments. Come closer and have a coffee with us to talk about it :)

[…] Have you read our text on motivation? Read before continuing. When we set a goal for someone to follow, we are directly attacking their autonomy and distorting their sense of purpose. Knocking on the goal and winning the incentives takes the place of purpose. […]

[…] Wanting experience doesn’t mean that you will work for free. We need money to live and want to be well paid. Yet companies insist in considering money (for themselves and for individuals) the ultimate goal. They don’t listen to what science is saying about human motivation. […]

[…] do the project if he doesn’t have a deadline! We’ve already covered this subject of motivation on our blog so I won’t go into it too much […]