Have you ever come across situations at work that look like soap opera? It may sound like office drama, but you may be experiencing the drama triangle, a social model of destructive interactions identified by psychologist Stephen Karpman.

A manager named Anita wants to implement new management practices in her department to give more autonomy to her team. She is demanded for results all the time by her boss and also by other areas of the company. Joyce is a marketing analyst and subordinate to Anita.

Anita faces the following situation: the control she once had over the people in the department is decreasing with the implementation of the new management practices in the group. Anita believes that people are not working as they used to and are not interested in the company’s results anymore, because they are taking advantage of the autonomy given to them.

Joyce, on the other hand, believes that Anita wants to innovate, but deep down she doesn’t want to lose her power. Joyce, thinks that Anita is sabotaging the implementation of the new practices and that everything is a farce.

Filling the Drama Roles

Anita decides to be hard on her subordinates. She begins to demand tasks and to ban some actions that she considers dangerous for the group. She thinks: I need to be tougher with everyone, otherwise the group’s performance will get even worse.

Joyce ignores the instructions passed by Anita and begins to do the minimum work necessary. She thinks: I need to keep my job, but I don’t believe what Anita says. I can’t do anything about it if the manager doesn’t want to change.

What happens then?

The office drama intensifies because neither Joyce nor Anita start a frank conversation with each other about their real needs. Focusing on judgments (Anita: People don’t work like they used to, Joyce: The manager just pretends that she wants to change), both create a dramatic dynamic in which nothing is solved.

By looking more closely we can understand that Anita and Joyce are two normal people, with needs and feelings:

Anita: I want everyone to see the good work I do. I want to be recognized for my skills. I don’t want them to say that I am responsible for the ruin of this group! (Feeling: fear)

Joyce: I want more freedom to do my job and show my potential. I want to be a creative force and not be seen as a machine that only performs instructions. (Feeling: frustration)

The Drama Triangle

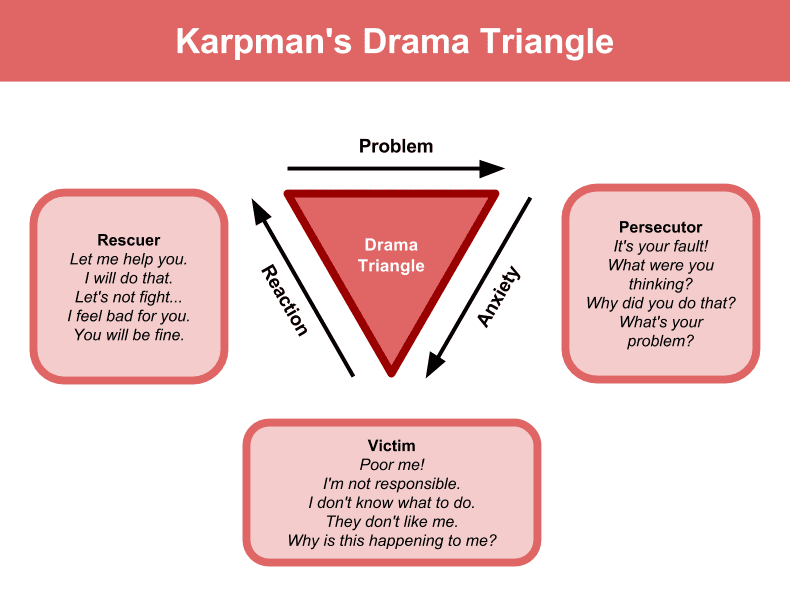

Karpman identified three destructive roles that people commonly take in conflicts:

- Victim: The (false) victim puts himself or herself as incapable of influencing the situation. He or she doesn’t feel responsible for the facts and prefers not to act, blaming people (or circumstances) for what happens. Victim’s favorite phrase: Poor me!

- Persecutor: The persecutor is oppressive, critical and authoritarian with the victim. He or she says: it’s all your fault! When realizing the damage caused, it’s common that the persecutor changes its role to rescuer.

- Rescuer: The rescuer appears to take the victim out of the conflict and solve his or her problem. He is sometimes empathetic, but deep down he has an undisclosed intention in helping the victim. It’s common for him or her to establish a relationship of codependency with the victim.

Note that drama doesn’t happen because of individual characteristics, but because of the relationships between roles that are filled by people.

A victim can’t remain in the role of victim without a persecutor or a rescuer. Roles complement each other in their dysfunction and don’t exist independently.

The motivation of each participant in the drama is to satisfy some unconscious individual need (or conscious and undisclosed). The problem is that the strategies to meet those needs are flawed and they don’t realize the damage that the drama generates in the situation as a whole. And of course, this happens a lot at work, the so called office drama.

It’s closer than you think

As I started to pay attention to the drama relationships, I began to notice a great temptation within me in filling the roles. I have a tendency to act as victim or rescuer in personal relationships and even as a consultant.

For example, as a facilitator of Cultural Design, it is good for my ego to have an opinion on the solutions proposed by the group and give an “answer”. But this can undermine work in the long run, after all my real role is to promote the emancipation of the group in relation to its cultural production. Giving the answer earlier can lead to dependency, and this is not what I really want.

Wondering how to get out of office drama? We will write in the next post about alternatives to the triangle.

[…] the post “Office Drama? Understand what’s behind it” we wrote about how conflicts in the workplace can intensify when assuming the roles […]

[…] the post “Office Drama? Understand what’s behind it” we wrote about how conflicts at work can intensify when assuming the roles Karpman’s drama […]