How on earth did we end up here?

The chain of command is incredibly ubiquitous in organizations, so much so that I have difficulty finding texts with theoretical and practical references for an organizational design that does not make use of it. And well, maybe that’s why I like to write things for this blog.

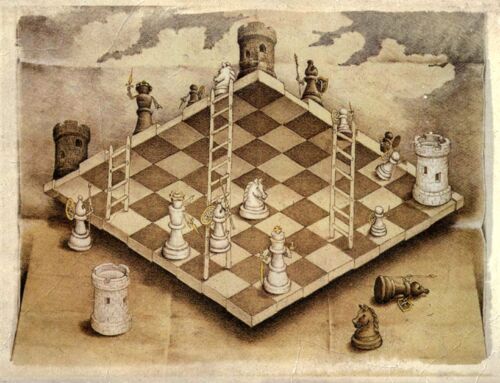

The chain of command (as a structural element), command and control (as a management strategy) and the hierarchy of command (as a principle) are so old that we need to go back centuries to find clues to their genesis and the reasons for their long existence.

Hierarchy and the emergence of civilization

We can say that the emergence of civilization and the hierarchy of command is concomitant.

Social hierarchy in human groups has its origins in hunter-gatherer groups, which had some sort of gendered division of labor. Of course, not all were like that, but it was common to have some incipient form of patriarchy (adult male rule) or gerontocracy (elder rule).

With the emergence of agriculture in various parts of the world, there was an explosive mixture of patriarchy/gerontocracy and resource abundance. In other words, agriculture and other technological advances allowed nascent hierarchies to become much more complex, authoritarian and violent. And what’s even worse, the military advantages inherent in agriculture—such as greater population density, resistance to disease from living with domesticated animals and metal tools—allowed the more developed hierarchies to exploit and conquer more territories with their armies.

It is within this context that the ideas and elements of command-and-control management arise.

The division of labour and the org chart

In 1776 Adam Smith advocated for the division of labor as a way to increase productivity. On a visit to a pin factory he speculated that a single worker could make 20 pins, however, if there was a division of labour and a processo of specialization and mechanization, that same worker could produce 4800 pins.

Alfred Chandler described in his book “The Visible Hand”, a hierarchy of command that was introduced in response to a train accident in the United States in 1841. The objective was to prevent accidents by controlling operations through the definition of responsibilities, with reports and verifications. These concepts were enshrined in an organizational chart where the chain of command was drawn as a line connecting boxes (positions). Today almost every company has something similar.

It was Frederick Taylor, in the first decade of the 20th century, who brought a scientific veneer to some well-known ideas. He said that methods were the exclusive territory of managers. It is the managers who must decide the best way to do things, and the role of the workers is to ensure that this is done.

Less than 10 years after Taylor’s publications, a German Max Weber described bureaucracy as the most efficient and rational form of organization. He believed that 6 essential elements were needed:

- Specialization and the division of labour;

- Hierarchical authority structures;

- Rules and regulations defining performance criteria;

- Recruitment based on technical and competence guidelines;

- Impersonality and indifference;

- A defined formal communication pattern.

However, Weber was also pessimistic about the impact of bureaucracy on workers. He could see the dehumanizing effects of the “iron cage” of bureaucracy that “succeeds in eliminating from the business world love, hate and all purely personal, irrational and emotional elements that are not possible to calculate.” His pessimism was spot on!

Success stories

Two narratives consolidated command and control in the management methods we know. The first was by Henry Ford, with his production line that led to cutting costs in half and doubling employee wages. Mass production for Ford was a dream.

A dream for shareholders and customers but a hell for the workers. In 1913 Ford needed to hire more than 50,000 people to maintain its factory with 14,000 workers. Work on the production line was monotonous and demoralizing, and it was in this context that unions grew, many of which depended on highly dysfunctional and conflictual types of relationships.

In the 1930s Alfred Sloan, an executive at General Motors, was trying to figure out how and where the most profitable areas of his company were. He proposed the creation of cost centers and business units, in addition to an idea that many still find brilliant, management by objectives. Sloan considered it unnecessary, or even harmful, for directors to know about the operation, if the numbers are bad, the unit manager is fired, if they are good, he is promoted. Luck, market and many other factors failed to enter into his analysis.

In short, the chain of command emerged to sustain and enhance a social hierarchy, and with the industrial revolution was praised as the main factor capable of generating efficiency and productivity. Nowadays, these reasons are beginning to be questioned, as we identify consequences that cannot be ignored.

The chain of command and the consequences of its use

The chain of command and all structures and practices related to the hierarchy of command have consequences for society and the organizations that make use of it.

Some of the consequences of using the chain of command are:

Intensifying injustices

Command and control dictates that people must work in positions designed by management and behave in accordance with the requirements defined by “leadership”.

This belief of how work should be organized justifies and maintains large disparities in pay and benefits for top executives. A CEO of a bank in Brazil earns 2000 times more than a bank clerk. By making use of the chain of command, we are reinforcing a culture that believes that power should be distributed unequally and therefore reinforces injustices.

Decreased capacity

The beliefs and practices that support the chain of command create a separation between who makes decisions and who does the work. And this limits the ability of organizations to generate value in sectors that involve knowledge or creativity.

It is incoherent, and needless to say illogical, for a knowledge worker to be forced to do something when he is actually paid to make good decisions. But that’s what the chain of command allows.

Let’s use the Chernobyl disaster as an example, the team operating reactor number 4 had the ability to avoid an accident limited by the chain of command. Deputy Chief Engineer Anatoly Dyatlov used his nearly unlimited authority, including threats, to force young subordinate engineers to make decisions that they believed proved to be disastrous.

Decreased adaptability

Currently, the VUCA reality demands that organizations be responsive and adapt quickly however, there are two phenomena that make this difficult.

The first has to do with the time it takes to make decisions. With the chain of command, it is common that decisions and information from the front line move up to where the managers make their final judgment on what to do. The problem with this is that it creates bottlenecks in decision-making processes and therefore slows things down.

The second is related to the maintenance of the benefits received. The chain of command promotes a competition for positions which have more authority, this competition is usually won by those who know how to please their superiors. When a person achieves a position of prominence and authority, a struggle begins to maintain it. When the organization encounters an opportunity that requires a turnaround or change of course, these leaders see their positions threatened. Any change needs to be scrutinized by managers who are afraid of losing benefits they have gained.

An emblematic example is of Alfred Sloan’s GM. A company that spent a good part of the 80s, 90s and 2000s in crisis, failing to reinvent itself. Even when it had an incredible opportunity to do so in the joint venture with Toyota – the NUMMI plant, but even so, it was not able to take what it learned and disseminate these practices to other units. The chain of command keeps things as they are, because those at the top are afraid of losing their position.

Dehumanization and unaccountability

The methods associated with the chain of command comprise a fabulous system of nullification of empathy and moral disaccountability of the subjects. It is easy for a human being to hold his superior or another authority figure responsible for his actions. This is what we hear in the daily lives of companies. It is expected that the manager is responsible for the acts of his subordinates and the consequences thereof.

This organizational arrangement makes possible abject and inhumane situations and events like the Nazi Holocaust. In his book Modernity and the Holocaust, Zygmunt Bauman emphatically concludes: “Indeed, the history of the organization of the Holocaust could become a manual of scientific management”.

Alternatives to the chain of command

If we want to organize work without using the chain of command, it is worth remembering that the absence of clear structures and agreements on power will not prevent it from accumulating and being mobilized by a small group. It just makes this process of concentration of authority veiled by politicking in the shadows.

Another way out would be to extinguish the possibility of someone making any decision alone that has the potential to impact a group, but this is also not a good alternative, as it disables and immobilizes a company or organization.

The strategy we propose and that we have seen used in several organizations, follows the following premise: we need clear and explicit agreements on how authority is distributed and we need good methods to keep these agreements up to date. It’s what we call The Art of Making Agreements.

There are some practices that are emerging in this field. The social technology O2 (Organic Organization) aggregates and establishes some of them and if you want to know more, check this out.

If you want to kick the chain of command and rebel against the status quo, Target Teal is here to help you on that journey. Let’s talk?

Translated by Tanya Stergiou

Leave A Comment